Philosophy Has Lost Its Way

I’m a late bloomer when it comes to philosophy.

The first time I read the work of a philosopher was less than five years ago, but I was hooked right away.

My first purchase was a collection of letters written by Seneca, a prominent Stoic thinker that lived two thousand years ago. His clear writing and timeless wisdom made an indelible impression on me, and I brought this book with me wherever I went.

Seneca’s words provided applicable advice on leading a life well-lived. Inevitably, his work led me to those of other Stoics, which then led me to Buddhism (the two schools of thought are very similar), which led me to Taoism – all of which further solidified my love for philosophy.

Before I read these people, I knew I enjoyed the subject, but didn’t make the effort to actually study it. I equated “pontificating” with “philosophizing,” so having rambling campfire discussions with friends about the meaning of life was enough to qualify me as a deep thinker in my mind.

However, studying the work of these great thinkers made me understand that my intuitions needed to be refined. You may be inclined to believe that you are an independent thinker with reliable intuitions, but without the sharp tool of timeless wisdom, your conclusions of the world are shoddily grounded by personal experience.

And if you rely solely on personal experience to draft your map of reality, be prepared to fall off a cliff when reality gives you an unpleasant update.

Upon realizing this, I thought about enrolling myself in a few philosophy courses at a nearby college to study it officially. But before doing so, I wanted to check out what the current state of the literature in the field was, and see what topics professors were addressing today. After all, my love for philosophy primarily revolved around the ancient thinkers, and that would only represent a small portion of the overall curriculum.

Well, what I found was enough to drop my desire from enrolling in any collegiate philosophy class.

Consider this abstract from a paper in the esteemed philosophy journal, Mind:

This paper first argues that we can bring out a tension between the following three popular doctrines: (i) the canonical reduction of metaphysical modality to essence, due to Fine, (ii) contingentism, which says that possibly something could have failed to be something, and (iii) the doctrine that metaphysical modality obeys the modal logic S5.

Or this abstract from another paper:

A consensus has arisen that ‘is like’ in relevant ‘what it is like’ locutions does not mean ‘resembles’. This paper argues that the consensus is mistaken. It is argued that a recently proposed ‘affective’ analysis of these locutions fails, but that a purported rival of the resemblance analysis, the property account, is in fact compatible with it.

Okay. What the hell are they talking about? How does this have anything to do with what it means to live a good and fulfilling life?1

I initially thought I was too stupid to understand the wise words of these higher minds, so I looked around to see what some philosophers had to say about the current state of the field. I didn’t have to search very far to see that many people were just as confused and dismayed by its direction.

The best critique of the field comes from UNC professor, Simon Blackburn (whose book Think is fantastic):

I sympathize with the ordinary reader – if there is such a person – who opens a contemporary philosophy journal, and can’t make heads or tails of what’s going on. I think that’s a terrible shame. Any educated individual who picks up Hume, Locke, or Berkeley can make a fist of what’s going on. That’s been lost, and that’s a pity.

In the world of academia, philosophy has become this weird playground of technicality and complexity that separates the curious masses from the intellectual elite. Instead of focusing on the timeless principles that increase human well-being, it has turned into a pithy battle about what certain words mean and whether or not a certain remark is true.

The greatest enemy of intellectual curiosity isn’t boredom, but needless complexity. Boredom can force you to look outside your comfort zone, but complexity constructs a stone wall barrier that intimidates and scares you away.

The stone wall around philosophy has gotten too high, and we need to take it back down. But first, we must identify the core problem, which stems from the often-confused relationship between philosophy and its famous friend, science.

Philosophy ≠ Science

Imagine that you want to build a car.

But then imagine that you have no idea what a car is made of, and where to even begin.

To build a car, you have to first figure out what type of raw materials are required to make it. Then you have to understand how to mix these materials together to build the individual parts. Then you’ll have to figure out how to engineer the various parts so they fit nicely to create the final product.

Building a car is an exercise in collecting factual information. Trial and error is of utmost importance, as experimentation is the key to getting you closer to the truth.

The process of building the car from the ground-up is called science.

Science tells us what the world is made of, how it works, and how we can use its components to build tools that help us understand it even better. It is the gathering of information and the rigorous filtration of it that leaves us with the end result: knowledge.

Perhaps the coolest thing about knowledge is that it’s iterative – whatever is true today can be refuted tomorrow. This means that progress ebbs and flows; there may be times where you surge ahead, but other times you will have to go back and revise some foundational assumptions that were made in the past.

If scientific progress was simplified onto a horizontal spectrum, it would look like this: There are just two primary states, but you will find yourself oscillating between them at various times due to the iterative nature of information.

There are just two primary states, but you will find yourself oscillating between them at various times due to the iterative nature of information.

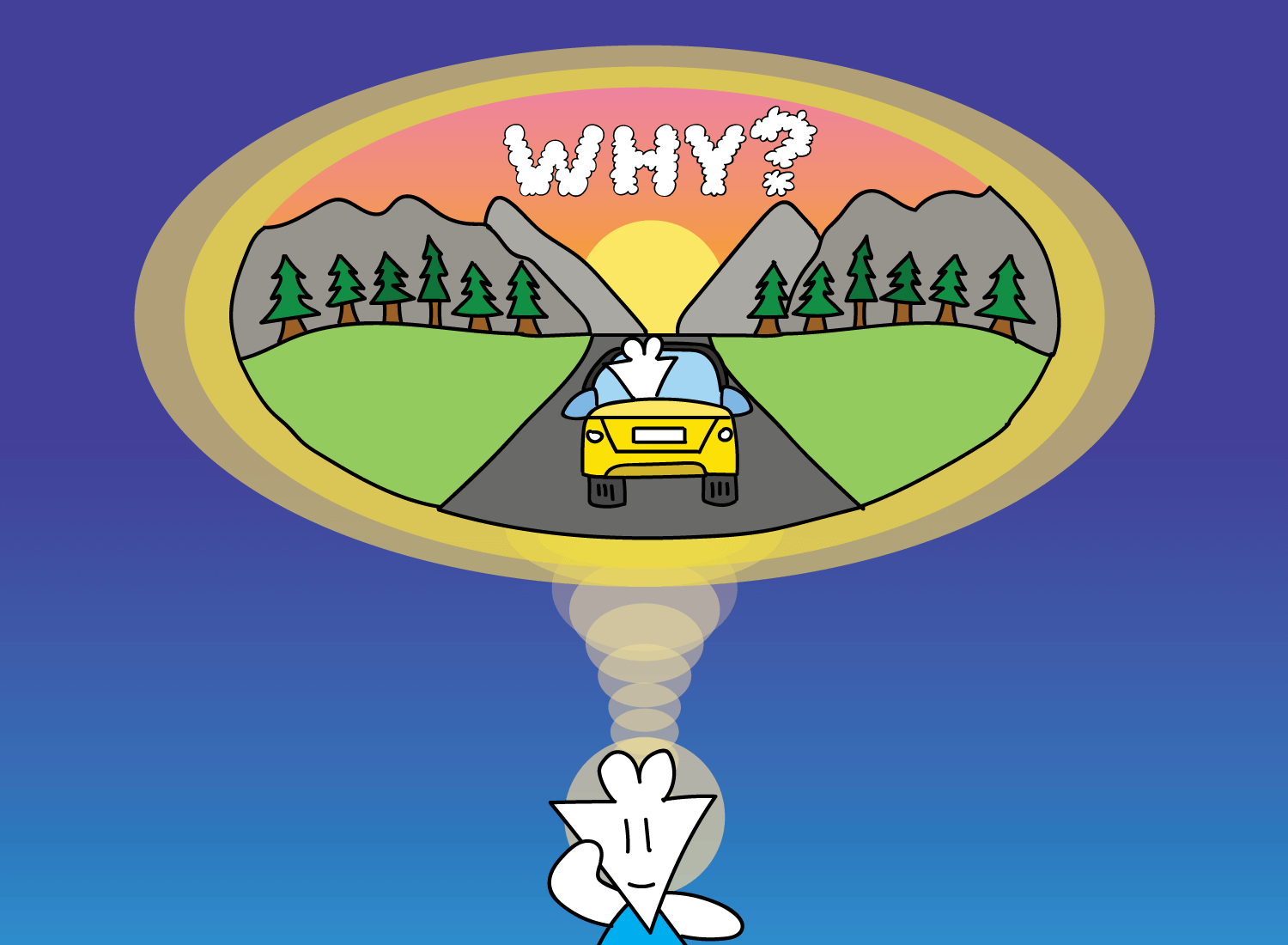

So once you’ve finished building the car, then comes the next logical question:

Where do you want it to go?

This is a question that cannot be answered through your knowledge of how a car is built. This is one that is determined by your inner values, or the things that are important to the question of well-being.

Science cannot tell you why you want to use your car to visit your parents, or why spending time with them is a top priority. It cannot tell you why you should use it to commute to work, or why making money is important to you in the first place.

The process of determining what to do with the car is called philosophy.

The goal of philosophy is to understand how you can use your factual knowledge to lead a life well-lived. If science gives us a beautiful photograph of the Earth, philosophy provides the realization that we are all in this game together. Now that you are more informed of how the world works, how will you position yourself to live a more fruitful existence?

If philosophical progress were simplified onto a spectrum, it would look like this:

Clarity of mind is the goal of philosophy, and wisdom is the manifestation of that freedom. Wisdom is the punchline that is delivered at the end of every Aesop fable, the takeaway one gets from any insightful work of science or art. It is the force that shapes personal values away from misery and toward well-being for oneself and others.

Clarity of mind is the goal of philosophy, and wisdom is the manifestation of that freedom. Wisdom is the punchline that is delivered at the end of every Aesop fable, the takeaway one gets from any insightful work of science or art. It is the force that shapes personal values away from misery and toward well-being for oneself and others.

Some may balk at this spectrum and say that philosophy is much more than the pursuit of wisdom. They might say that philosophy is not defined by some cliched search for the deepest questions of meaning. They will proclaim that it is a hard science, as it tries to uncover the underpinnings of the mind and reveal truths that can only be discovered through experimentation.

Welcome to the root of the problem with philosophy today.

All too often, philosophy is viewed as a science, which leads to the tendency to place the two spectrums parallel with one another:2

There is a big problem with overlapping the “how” questions of science with the “why” questions of philosophy, and it has to do with the differing nature of progress in both fields.

Here’s Simon Blackwell again in eloquent form:

If philosophy had a string of cumulative results to its name – as physics does and biology does – and we unmistakably know more than we did a couple of centuries ago . . . [then] I accept the parallel [between philosophy and science].

But there’s no evidence that it is like that.

Very basic questions keep recurring and being handled again and again in different ways. So the more apt comparison I see would be with humane studies, like with history and literature – perhaps art itself.

Science is an incredibly timely discipline, meaning that there have been clear benchmarks of progress in our march toward modernity. The “how” questions tend to have definitive answers that compound and lead to further advancements in the field.

The question of how doctors were seeing such high infant mortality rates after handling cadavers was explained by the germ theory of disease. The germ theory then led to the rise of antiseptics, which emphasized the importance of sterilization for infection control. There is a clear track record of successes in science and an overcoming of past failures – we will never go back to a time where washing one’s hands is seen as a dumb thing to do.

Philosophy, however, is a timeless discipline, meaning that the questions that were asked thousands of years ago are still unsolved and relevant today. The “why” questions about existence don’t have definitive answers, and we will spend all of our lives trying to sort through them.

The question of why we’re here (aka the meaning of life) is just as relevant and pressing today as it was in ancient times. The question of happiness is something that refuses to have a clear and cogent answer, yet we will never stop asking it.

In philosophy, it is often the pursuit of the question that is more interesting than the answer, and this paradox is what makes the field much more of an art, and less of a science.

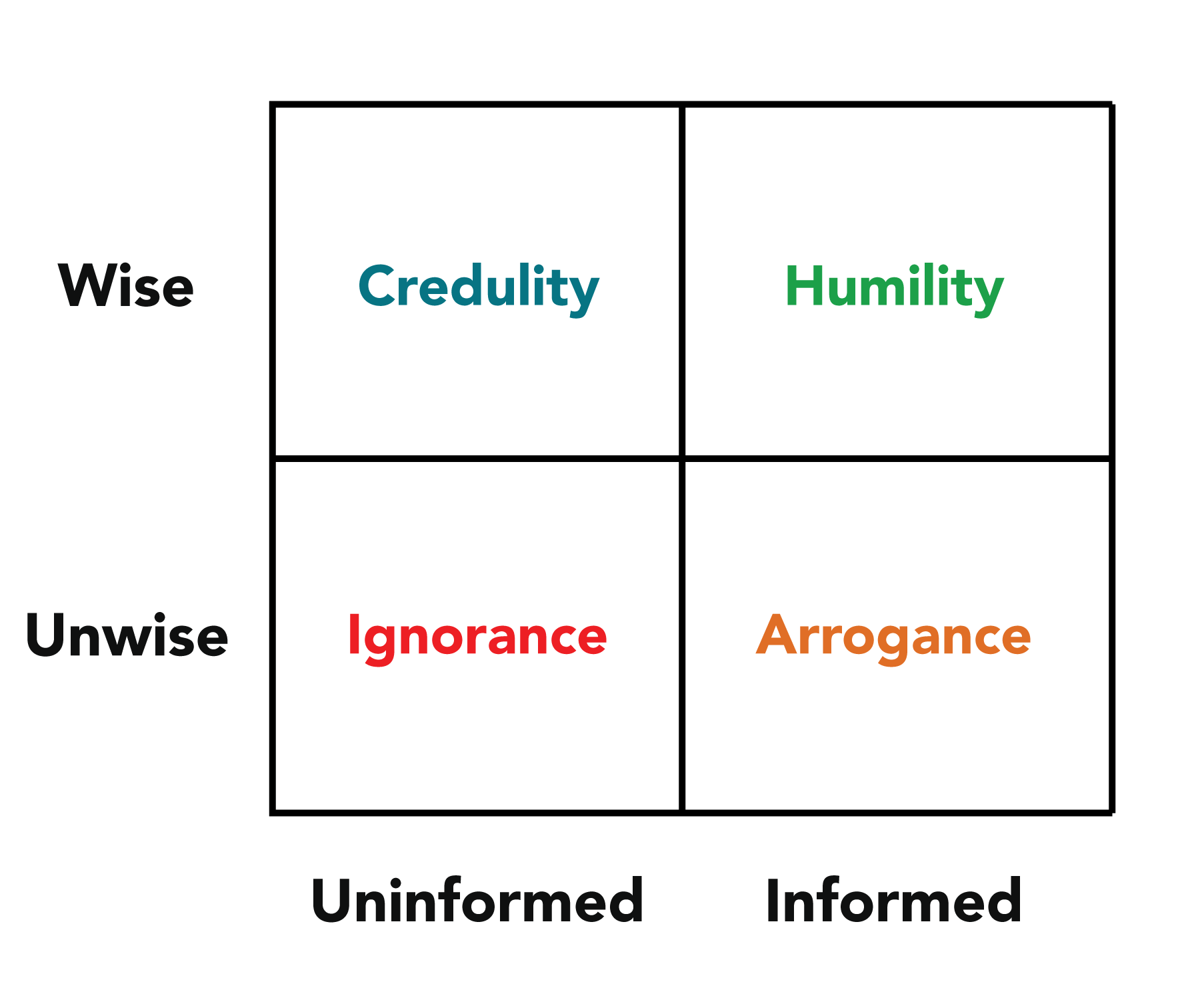

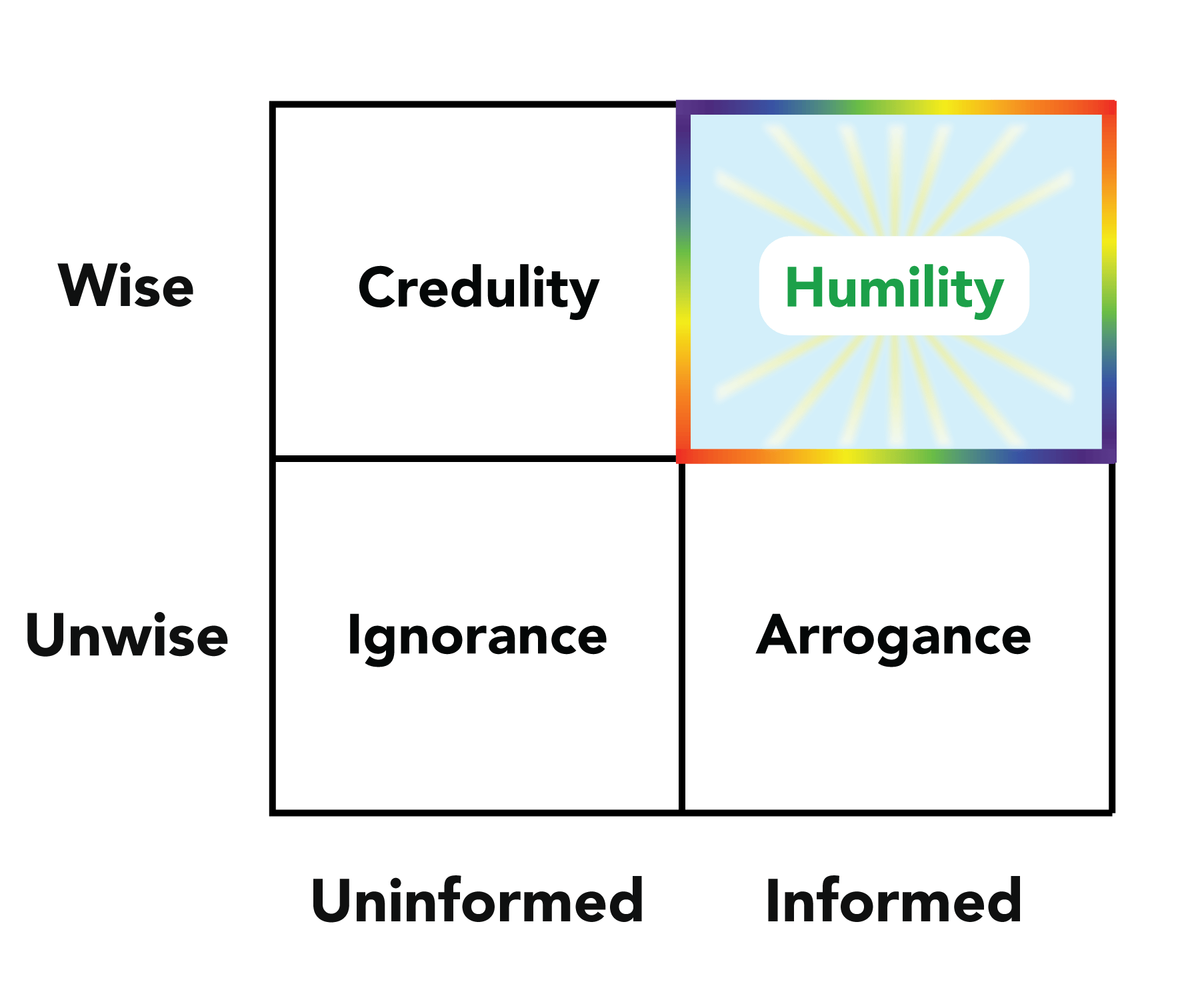

Rather than mapping science and philosophy onto a singular dimension, we must place them in separate ones, creating a two-dimensional axis that paints the real picture:3

Combining the primary qualities of each axis yields four views:

Combining the primary qualities of each axis yields four views:

Ignorance is the lack of knowledge and the lack of wisdom. Not only are you content with accepting personal experience as your bible, you have no desire to examine your own life in any detail whatsoever. In short, it’s not a good place to be.

Credulity, or the tendency to be driven by belief, can be the lack of knowledge despite the possession of wisdom. This may sound like an odd combination, but we see evidence of this everywhere. A good example may be a person who rejects the theory of evolution, but has a sound moral center and regularly reflects on how his life is progressing. A hard dismissal of science doesn’t necessarily mean you’re unwise, but it certainly means you’re uninformed.

The final two views – humility and arrogance – directly address the problems of philosophy, and much of academia in general. Let’s start with arrogance, and how that manifests its way through the field.

The Arrogance of Complexity

When you’re first introduced to a complicated topic, it can feel like you’re wading through a ton of loose blocks that are all over the place:

But then you start reading the literature on it, and things start coming together to form a structured body.

This eventually coalesces into a foundational building block…

… that can then be used to understand higher-level concepts in the field:

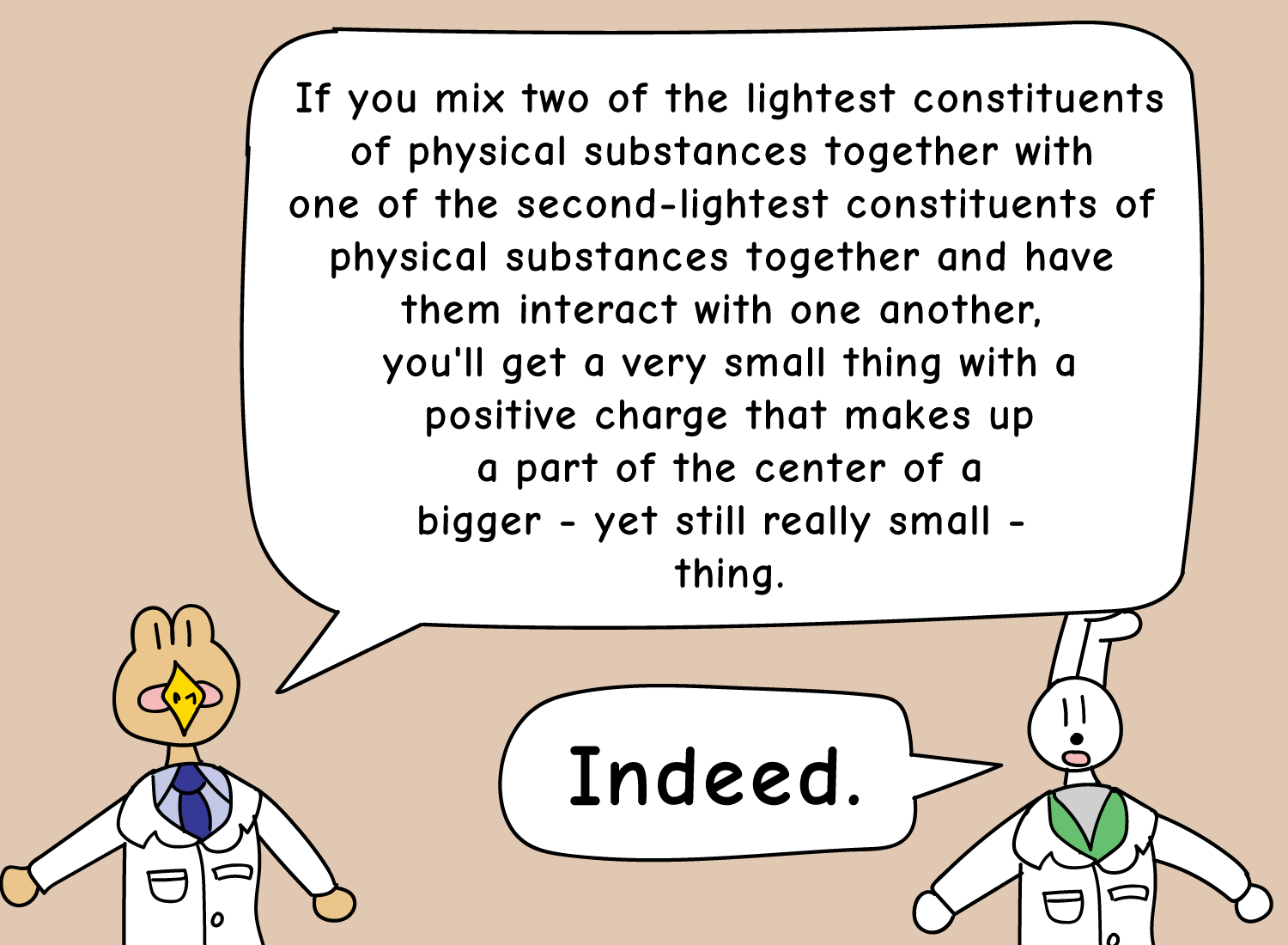

In the hard sciences, it’s important to simplify some of these building blocks into terms that can be recalled when attempting to explain higher-level concepts. For example, instead of referring to a quark as “an elementary particle that is the fundamental constituent of matter,” physicists just call it a quark. That way when they try to explain a higher-level concept like a proton, they can simply refer to it as a collection of quarks.

These condensed, field-specific terms are called jargon.

Jargon is important when it comes to explaining objective reality, which is an iterative exercise in observation, experimentation, and communication. Without it, scientists would have to needlessly explain everything at its most granular level, yielding a word salad that would be frustrating to sort through.

As noted earlier in this post, science has a string of successes to its name, so jargon is a necessary byproduct of this type of iterative knowledge. However, jargon isn’t good for popularizing science, as most people don’t have the experience of building their scientific knowledge from the ground-up with their own methods of experimentation.

This is where scientific communicators like Carl Sagan, Neil deGrasse Tyson, and Kurzgesagt (my favorite YouTube channel) come into play. They are able to deconstruct the blocks of jargon into easily digestible pieces that people can relate to, which allows the masses to find fascination in the concepts that were once intellectually inaccessible to them.

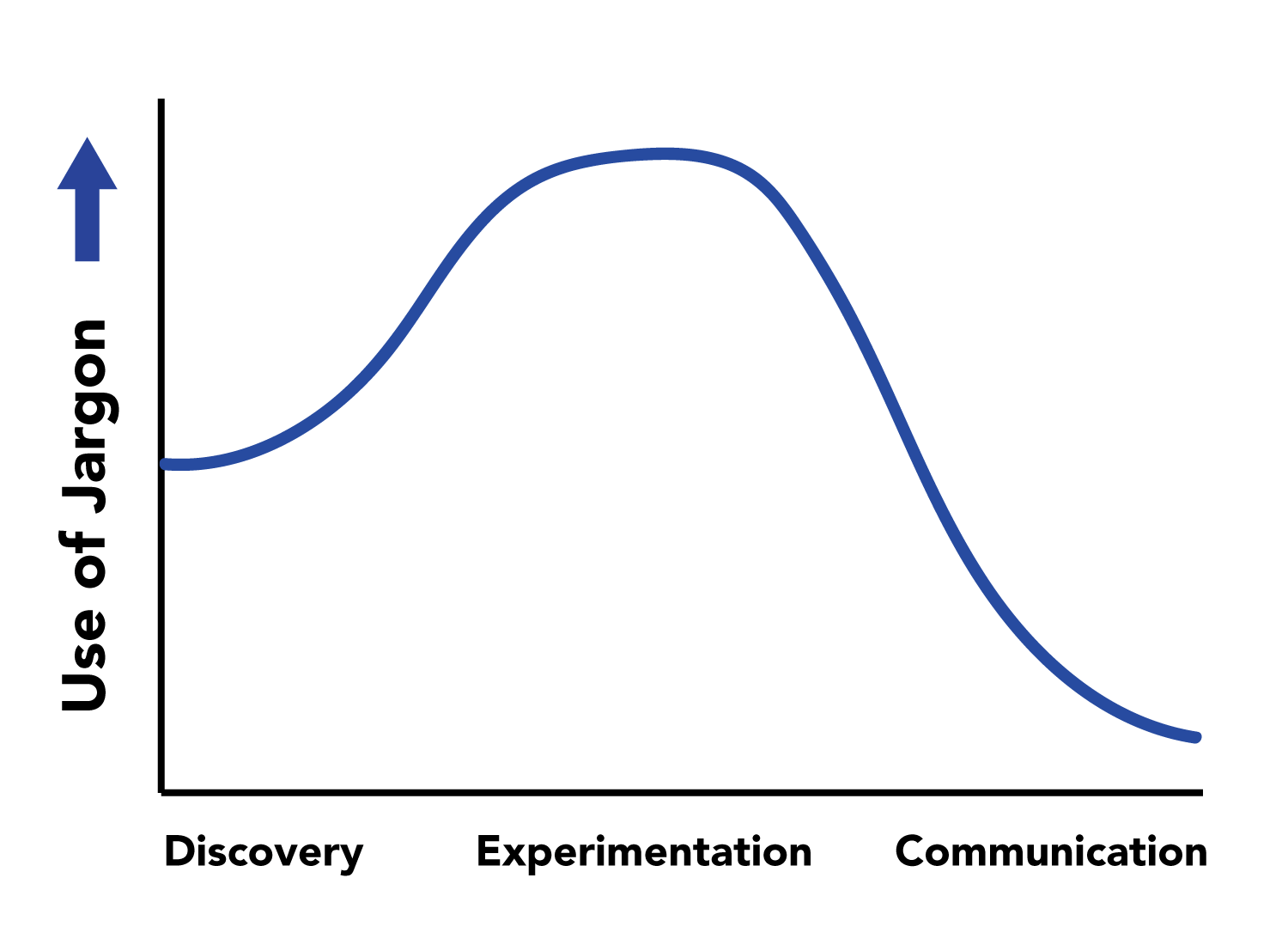

If we were to map the cycle of scientific progress vs. the use of jargon, it would look like this:

Jargon is effective at the ground-level for sorting through vast quantities of information among peers, but terrible for communicating any findings to a general audience. A wise scientist is one that knows how to oscillate between the two modes of dialogue at any given moment.

Now let’s bring philosophy back into the picture.

Philosophy is not a science, so it is not grounded in the scientific method. Philosophers do not test theories using empirical data, they don’t use research subjects to draw conclusions, and they sure as hell don’t have labs.

Instead, philosophy is the study of one’s values, making it a question of well-being as opposed to scientific proofs. Its primary purpose is to understand what it means to live a life well-lived, and this comes from deep reflection and subsequent communication of those thoughts with others.

In science, communicating an idea to the masses is only a part of the picture, but for philosophy, this communication is everything. The greatest thing a philosopher could do is to make her wisdom accessible to anyone, no matter how complicated her thoughts may be.

True philosophers make their ideas relatable to others, which means they turn down the jargon and turn up their shared humanity. Even though their worldviews may be constructed with a unique lens, they make the effort to understand the similarities they have with the audience they’re addressing.

Or as Seneca puts it:

Within, let us be completely different, but let the face we show to the world be like other people’s.

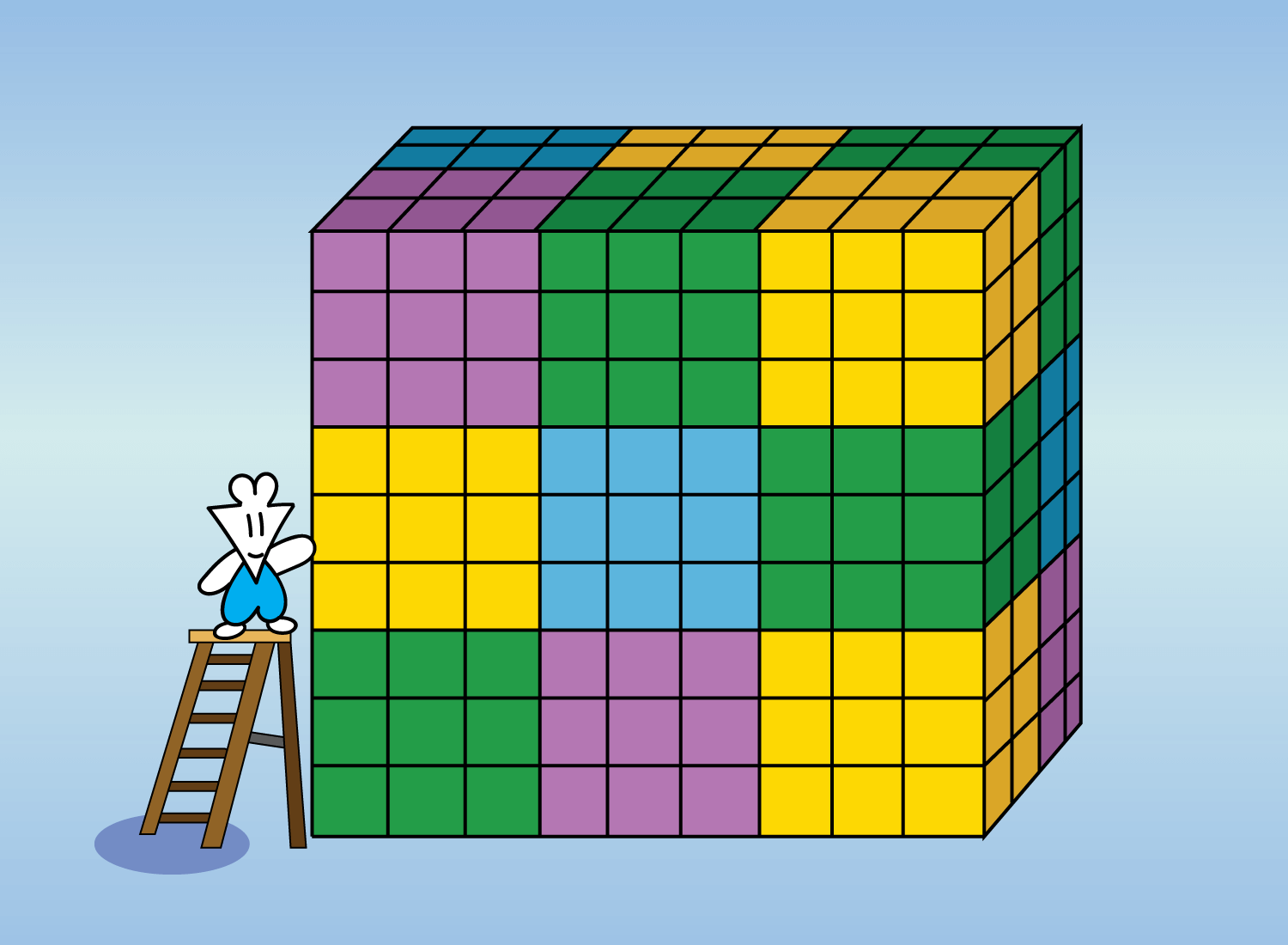

A humble philosopher works hard to make their ideas simple and accessible:

While an arrogant philosopher tries to sound smart by making things needlessly complicated:

When wisdom is communicated to others, the line between humility and arrogance is thin. If done right, it can be immensely valuable and boost the well-being of so many people. If done wrong, it can make you look like an intellectual asshat that scoffs at the inferiority of others.

The key is to remember that philosophy is an art, not a science. The questions we’re trying to answer have less to do with atomic structures, and more to do with mental resilience. We don’t need complex proofs and equations to get there; just a keen understanding of our shared humanity will suffice.

The Wisdom of Simplicity

When I think about the correlated nature of wisdom and simplicity, I’m reminded of this neat visual:

The themes explored in Hemingway’s work were difficult and complex, but his genius was in having the humility and patience to deliver them in a way that even a 4th grader could read.

Philosophy follows the same principle.

There’s a reason why the ancient thinkers of the past continue to be impactful today. The Buddha’s clear and succinct teachings permeate the mindfulness movements that have swept the West, and the digestible writings of the Stoics have helped countless people navigate the problems of modernity.

These ancient thinkers discussed the timeless issues that actually mattered, instead of the pithy issues that are debated within the halls of academia today. Rather than reflecting on real problems of the human condition, contemporary philosophers are writing essays on how to decipher the word “water,” or whether or not holes exist.

In today’s age of abundance, we are experiencing a world we’re not equipped to handle. Rates of depression are steadily rising, and suicide rates in the United States are following a similar trend. Philosophy is needed more than ever, but the ivory tower of complexity is distancing the masses from its utility.

Socrates famously believed that everyone should be a philosopher, and advocated for people of all backgrounds to study and talk about it. He likely observed that the real philosophers were the everyday people that could clearly communicate their struggles, and not the intellectual elite that spewed gibberish to put themselves on a pedestal.

2,000 years after his death, his words remain more relevant than ever.

_______________

_______________

Related Posts

If you want to delve into the questions of philosophy that actually matter, you can start with these posts:

Socrates: The Badass Godfather of Uncertainty (“What does it mean to live an examined life?”)

Do You Really Believe What You Believe? (“How do I know that I’m not deceiving myself as I construct my beliefs?”)

What Makes Death Bad? (“Death is inevitable, so why are we so terrified of it?”)